(Cross-posted from my blog, Understanding Social Change)

For those of us interested in progressive social change, things can seem demoralising sometimes. We often see setbacks, such as when the UK government announces new oil and gas licences, even when experts agree that further oil and gas exploration is not compatible with plans to keep global temperatures under 1.5 degrees, in line with the Paris Agreement. If not setbacks, painfully slow progress is also common, such as the gradual plateauing of animal consumption in the UK.

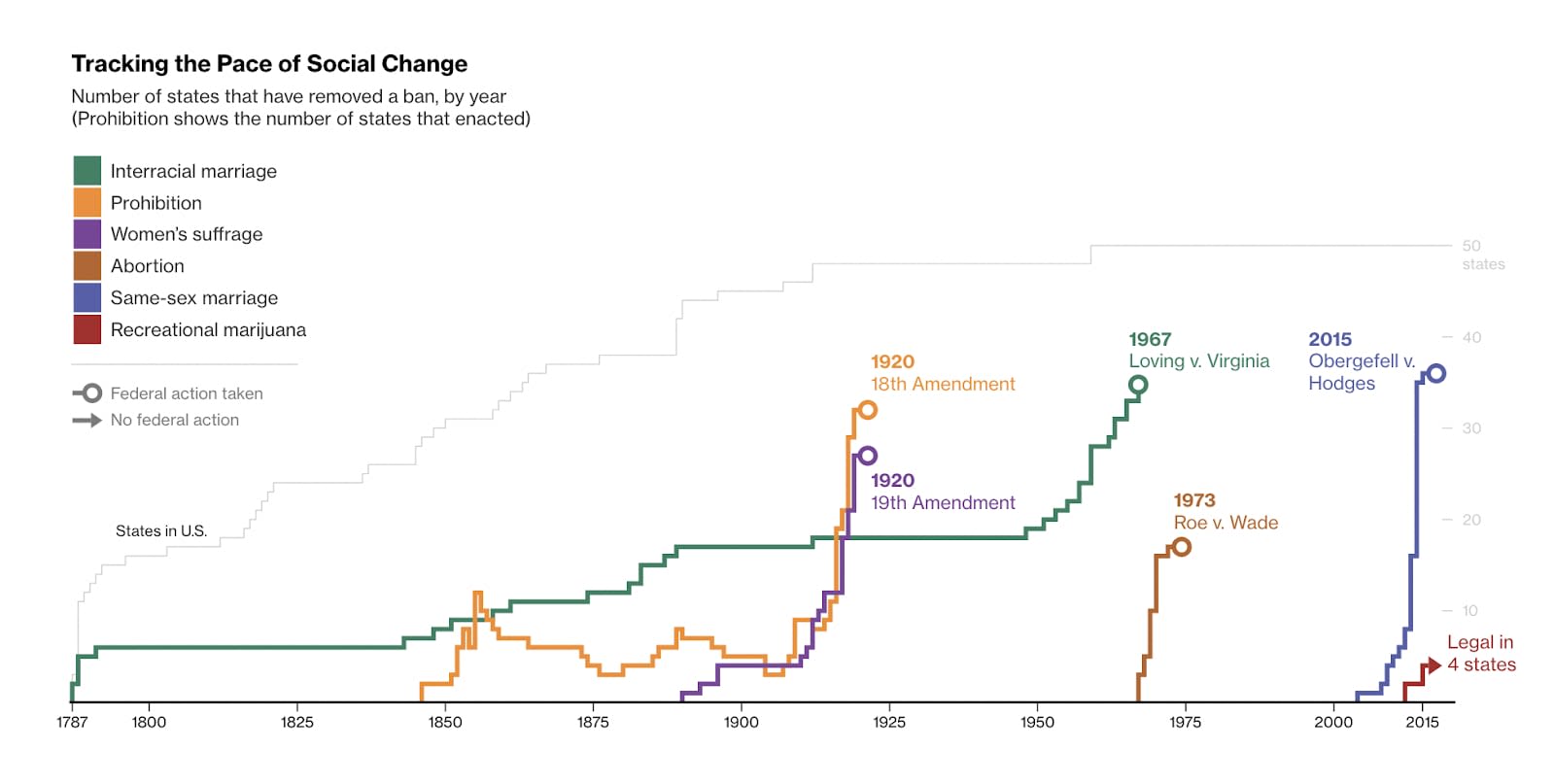

A common concept invoked by activists to keep morale high is the idea of social tipping points. In a nutshell, it is the idea that when a committed minority of people adopt a belief or behaviour, this can spread rapidly through society. It supports the idea that change can seem painfully slow for a long time, and then suddenly everything changes at once. This is reassuring for activists who have been campaigning diligently for years, with little avail. A neat graphical demonstration of this can be seen below when applied to US state legislation on various social issues (source here).

Most obviously, in issues such as same-sex marriage (characterised by the Obergefell vs Hodges case) or women’s right the vote (the 19th amendment), things moved slowly, or even sometimes in the wrong direction, for decades, before a sudden flurry of activity led to an increasing number of state-wide wins, culminating in a national level win.

This is an inspiring story for activists and those campaigning for social change – it means it’s okay that we don’t see the fruits of our labour instantly, or even incremental wins taking us in the right direction. Our hard work may still be paying off, but social change is messy, and things take time. All of these things are almost certainly true. However, it can also lull us into a false sense of optimism, by allowing us to think that we’re winning, and results take time, where the reality is that we’re not making any meaningful progress.

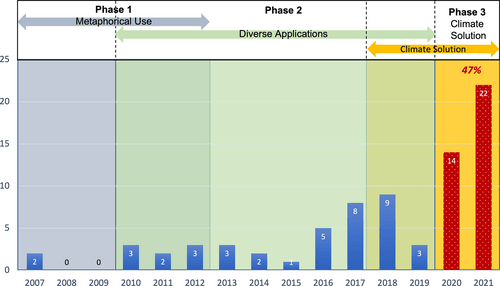

There are several examples of putting a lot of belief in social tipping points in society, whether it’s in popular media outlets, social media forums, academia or civil society groups. (Since publishing this originally, Chris Bryant mentioned potential tipping points around veganism in this Veganuary piece in the Conversation - I remain sceptical due to the reasons below!) This paper, bringing a much-needed critical look at the scientific landscape of social tipping points, finds that 47% of all papers referencing social tipping points were published in 2020-2021, focusing on them as a climate solution (e.g this popular one by Simon Sharpe & Timothy Lenton).

I think this mentality of social tipping point-based optimism is neatly summed up by environmental journalist and campaigner George Monbiot, who says:

“My own belief is that our best hope is to precipitate a social tipping: widening the concentric circles of those committed to systemic change until a critical threshold is reached, that flips the status quo. Observational and experimental evidence suggests the threshold is roughly 25% of the population”.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but I want to mainly focus on his last statement, that experimental evidence suggests the threshold for social tipping points is around 25% of a population being a committed minority and trying to overturn conventional norms. This statement comes from the 2018 paper, Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention (un-paywalled version here), by Damon Centola et al. If that name rings a bill, Damon Centola is also the author of the popular book Change, which covered similar topics.

I have some issues with this paper, and particularly how it’s been communicated by the authors and mainstream society. Most egregious might be press releases and articles by the lead author and his university, with headlines like: “Tipping point for large-scale social change? Just 25 percent” or “The 25 Percent Tipping Point for Social Change”

This has led to this 25% number popping up in lots of places, whether it’s George Monbiot’s columns, Scientific American, The Atlantic, or Harvard Business Review. More anecdotally, I’ve recently heard often mentioned with climate activist circles as a reason for optimism given the slow progress on climate (possibly helped by George Monbiot’s popular Twitter thread).

So, I wanted to examine this 25% number, to see if it holds up to the big claims made above. Long story short, this paper provides extremely little evidence that 25% is a likely number for social tipping points, for issues that people actually care about.

First of all, there is the easy critique that this answer is so absurdly simple, that this cannot be true. How can we expect social change, across a variety of different issues, cultures and times, to often converge at a single, round number? This is far too simple and sadly, our world is far too complex.

The more nuanced critique involves looking at the methodology, which is sadly not discussed enough in popular articles (although, Wired and The Atlantic to their credit, do give some discussion of the methodology and its limitations, but sadly, not enough).

The paper arrives at this 25% figure using two methods, an experimental set-up, as well as computational modelling. I’ll focus on the experimental test, given the computational modelling is very likely above my pay grade.

In short, the experiment created 10 independent online groups, ranging from 20 to 30 people, drawn from a random pool of 194 study participants. Pairs of people would be drawn from within the 10 groups and matched, where they were assigned a photo of a face and encouraged to coordinate by guessing a name for that face.

If both individuals in the pair guessed the same name for the face, they would get a reward of $0.10 for coordinating, and lose $0.10 if they didn’t coordinate (but they couldn’t lose money overall, obviously, otherwise that would be a hard sell to get people to join your research study). I’ve attached a screenshot from the paper’s supplementary materials below, so you can see what the participants experienced.

Initially, the game was run until all players would reliably associate a face with a name, and there was some equilibrium reached (e.g. Mary above).

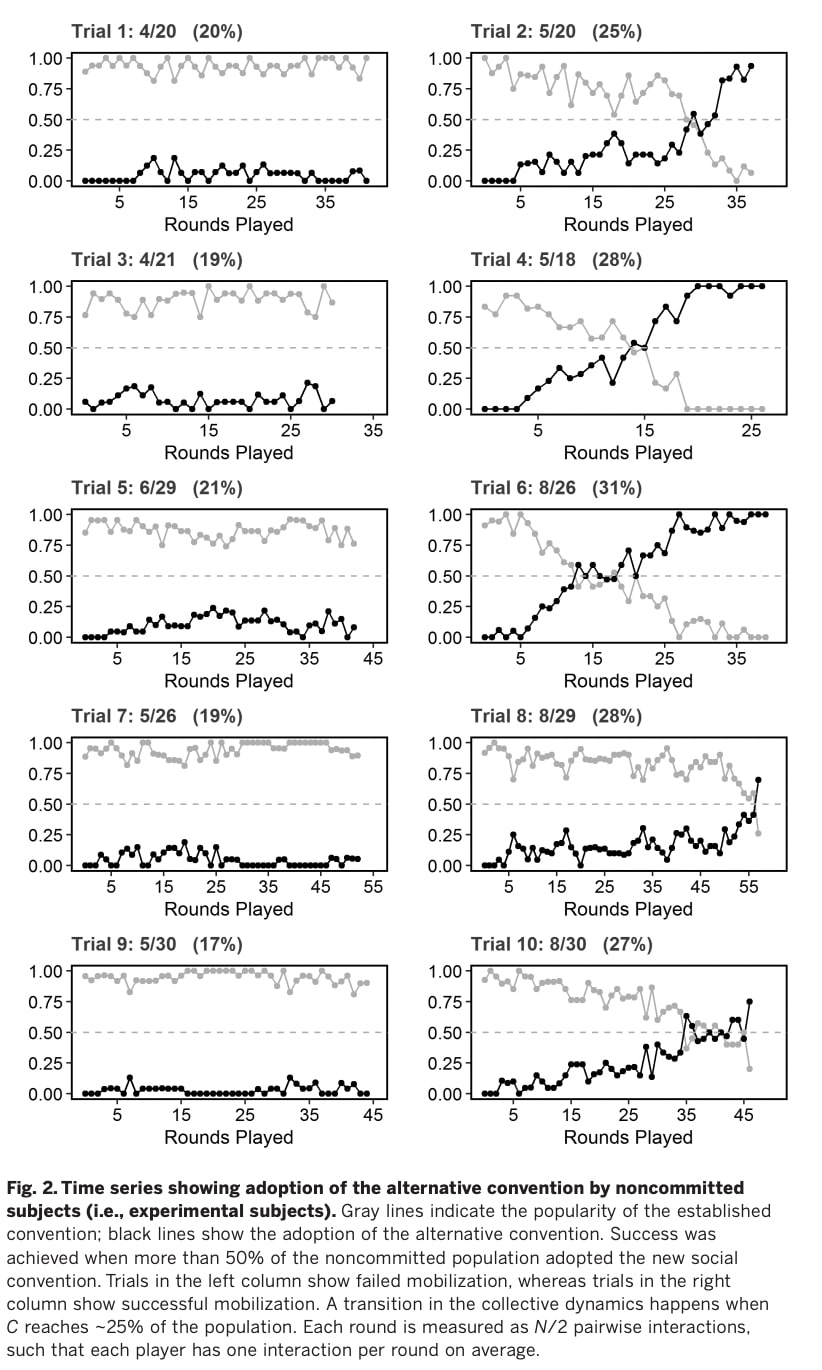

How does this actually answer the question of when we should expect social tipping points to occur? The answer lies in the (clever) experimental design that comes next, where each of the 10 groups was now injected with some variable percentage of confederates, or a “committed minority”, who all wanted to give an alternative name for the same face (e.g. Sarah, rather than Mary). For example, the percentage of confederates trying to overturn the established norm varied in these 10 groups from 17% to 31% of the total population. Using this, Centola et al. could mathematically observe at what percentage of the total population the broader group shifted from their pre-established norm to their new norm (e.g., from Mary to Sarah).

Centola et al. find that this percentage where the committed minority would overturn the established norm (read: the name people were originally assigning to this random face) was around 25% of the total population, hence this neat 25% finding. You can see a nice graphic of the results below (and as before, the full paper here).

Let me start by saying I think this is a very neat experimental design, and it’s certainly interesting. The issue I have with this paper is the claims that this will generalise, in any way, to broad social issues people are referring to, whether it’s climate change, meat consumption, anti-racism, or something else.

Hopefully, now that people have seen the experimental design, it will be fairly obvious why I think this paper is far too artificial to be of much real-world relevance. However, I’ll pull out a few key points as to why I think this approach is far too simplistic to be meaningful:

- Assigning names to random faces is not representative of the issues we care about. Specifically, when talking about changing attitudes or behaviours, they are often tied to things that are culturally or societally ingrained e.g. eating meat is part of our tradition, flying for leisure is totally acceptable, we all aspire to own a car, and so on. These beliefs and behaviours are much harder to detach than “Oh, I called this random face Mary last time and these people really want it to change to Sarah, so I may as well go along with it”. This, most importantly, I think devalues the applicability of this research to real-world issues. Even in a much simpler dynamic of picking reusable mugs over single-use cups, research finds a tipping point of between 50-65%, far higher than the 25% proposed by Centola et al.

- People were incentivised to coordinate – this doesn’t happen in reality. In this game, people were given $0.10 every time they coordinated, which, as you might expect, probably has a very positive effect on coordination. When people are incentivised by the experiment, it’s impossible to tell whether people actually changed their beliefs, or they are simply pretending to receive additional cash rewards.

- In reality, this is almost the polar opposite of what we might expect for some of the social issues we care about. For example, electric vehicles are often more expensive than internal combustion engine vehicles, and planet-and-animal-friendly meat alternatives are more expensive than animal products. So, people are disincentivised from adopting these pro-social behaviours, rather than incentivised to adopt them.

3. Life isn’t a series of one-shot interactions. I’m stealing this point from this great blog post by Peter Licari, which also provides a reality check on this paper and the way it was framed. In short, this study works by pairing people up in 1-on-1 scenarios, whereas this is a relatively rare interaction in society. In reality, we build our ideas of social norms and acceptable behaviour by talking to family and friends (often in groups), reading social media (e.g. Twitter, where everyone can join in), or reading the media (where it’s a one-to-many interaction).

Overall, I think this is a neat paper, and I would be very happy if I published it! However, I’m worried that people read the headlines, fail to understand the methodology and develop some ill-placed belief that social tipping points will solve the world’s issues. Of course, they might, but this paper certainly doesn’t make me feel much more confident about it.

I’m not trying to be a doomer here. I think progress on some of these very challenging problems, be it climate change or the trillions of animals killed for food each year, is possible. However, I believe we need to have a level-headed assessment of how our issues are progressing, be it negative or positive, to better strategise and achieve change.

--

(P.S. Damon Centola’s book Change, which covers similar topics, is a much more reasonable and non-hyperbolic overview of some of the literature and power of social networks. )

Thanks for writing and sharing! This was a useful debunking of something I hear a lot too.

Tipping points may be overrated, but I still think they can be appreciable force. Here are two reasons why:

I think these kinds of dynamics underlie the rapid legislative victories outlined in the first chart in your blog post, although Loving vs. Viriginia is an interesting counterexample).

What I do find lacking from a lot of tipping point discussion is more consideration of the underlying mechanism supposedly fueling the self-propelling tendency. In new technology adoption, it is often more clear ― increasing returns to scale on the production and consumption side are a big one. For social norms, for me at least it's often less clear how, where and why beliefs propagate in society.