TL;DR: Global performance indicators (GPIs) compare countries' policy performance, encouraging competition and pressuring policymakers for reforms. While effective, creating GPIs carries risks such as public backlash. However, certain characteristics can mitigate these risks and enhance GPI success. Proposed is an organization dedicated to creating GPIs for animal advocacy, ranking jurisdictions based on impactful animal welfare policies.

You can also read this report on Animal Ask website and the EA Forum

Executive summary

Global performance indicators (GPIs) are sets of rankings in which the performance of various countries or states in a given policy area are compared. GPIs can be used to stimulate competition between countries or states, thereby placing pressure on policymakers to enact particular policy reforms.

The evidence shows that GPIs can cause policy change, at least in some cases. There are some risks to creating GPIs, like the risk of triggering an emotional public backlash within a country. There are many characteristics that can help increase the chance that a GPI will be successful in its goals and decrease the chance of backlash.

Here, we consider establishing a new organisation whose sole purpose is to create GPIs for use in animal advocacy campaigns. This organisation would create new GPIs that rank jurisdictions against each other on the basis of the animal welfare policies that can do the most good for animals. For example, GPIs might focus on key welfare protections for farmed chickens, fish, or shrimp, or on government policies that support plant-based foods.

Overall, we believe that it is indeed worthwhile for the animal advocacy movement to establish a new organisation that creates GPIs for use in animal advocacy campaigns. Establishing this organisation is a relatively small investment for the movement (a couple of full-time staff members), and the GPIs would improve the probability of success for existing animal advocacy campaigns around the world. Given the potentially large benefits, making this small investment appears to be a great deal.

1. Introduction

1.1 What are global performance indicators (GPIs)?

Global performance indicators (GPIs) are sets of rankings in which the performance of various countries (or states, supranational bodies, etc) in a given policy area are compared. GPIs are used, at least for our purposes, as a lobbying tool - by stimulating competition between countries or states, GPIs can place pressure on policymakers to enact particular policy reforms. GPIs also attract attention from the media and the public, making them one way to keep particular policy issues on the political agenda.

GPIs are also known as rankings, indicators, indices, composite indices, scorecards, or performance assessments. They exist in virtually all policy areas, from climate to corruption to human rights (1). It should be emphasised that we are here discussing GPIs as a political tool for placing pressure on policymakers, not as a scientific tool (1).

1.2 GPIs in animal advocacy

World Animal Protection produces the Animal Protection Index (API). The API provides a letter grade for 50 countries on the basis of their animal protection legislation. The API is frequently cited in the media, and we have heard from many animal advocacy organisations that the API has been a helpful tool during corporate relation campaigns. However, there will always be limits to what any one indicator can achieve. The main limitations specific to the API are:

- The API has a very broad focus, meaning that it is not targeted towards specific policies. This might make policymakers less keen to adopt the lessons from the API.

- The API includes all types of animals affected by humans. This may dilute the message and draw attention away from the most high-impact policy areas (e.g. farmed chicken and fish welfare).

- The API operates at the level of countries. This is useful for countries where the national government has jurisdiction over animal welfare policy; however, in many countries, it is state or subnational governments that have most of the power over animal welfare. In countries where power over animal welfare is held by state governments, it may be more effective to produce indicators ranking the different states.

- The API only measures 50 countries, meaning that it cannot be used by animal advocacy organisations in the rest of the world's countries.

- The API is only updated every few years, rather than every year. This means that the API has fewer opportunities to gain media attention for animal welfare policy.

- The Voiceless Animal Cruelty Index builds on the Animal Protection Index by focusing more explicitly on farmed animals. The index includes measures for the total volumes of production and consumption of meat and animal products in countries, penalising countries with higher rates of production and/or consumption.

- Animal Legal Defense Fund publishes the U.S. State Animal Protection Laws Rankings. This GPI is subnational, comparing different states within the US against each other on the basis of their animal protection legislation.

- Sandøe et al. show how benchmarks can be used to compare the performance of western European countries in animal welfare during pig production and broiler production (2–4). This was mostly an academic/educational exercise, but it gives an example of how countries can be scored on pig and chicken welfare.

- The Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare assesses the animal welfare and regulatory performance across 37 criteria of the top 150 largest food companies. This benchmark targets companies, not governments.

We are aware of four other GPIs in animal advocacy:

1.3 Should we launch a "GPI Squad"?

For this approach, we consider establishing a new organisation whose sole purpose is to create GPIs for use in animal advocacy campaigns. This organisation would create new GPIs that rank jurisdictions against each other on the basis of the animal welfare policies that can do the most good for animals. For example, GPIs might focus on key welfare protections for farmed chickens, fish, or shrimp; alternatively, GPIs might focus on government policies that promote plant-based foods. The GPIs could also involve weighting criteria such that the GPI scores are a proxy for the total animal suffering caused (e.g. chicken and fish protection laws carry greater weight than cow protection laws).

These GPIs could be created at various levels, whether global, regional (e.g. all countries in the EU; or all African countries), or subnational (e.g. all states in Australia). The organisation would then circulate these rankings among local animal advocacy organisations to encourage the rankings' use as a tool in campaigns. A greater number of GPIs would mean that any given jurisdiction has a greater chance of scoring poorly by any one GPI, and therefore having a GPI that can be adopted by animal advocates for campaigns in that jurisdiction. Furthermore, GPIs could be specific to regions (e.g. western Europe; south-east Asia) - regional GPIs could increase the competitive spirit among regional rivals wanting to perform well, and regional GPIs could ensure that policy improvements are seen as more achievable by policymakers (5,6).

A GPI squad would be a hits-based approach. Many of the new GPIs might have minimal impact, but a handful could have enormous impact by triggering policy reform in a country.

Campaigns rarely get cheaper than this. A GPI squad would basically require a couple of full-time staff members with an internet connection, plus some way to circulate complete GPIs to animal advocacy organisations in the relevant jurisdiction(s).

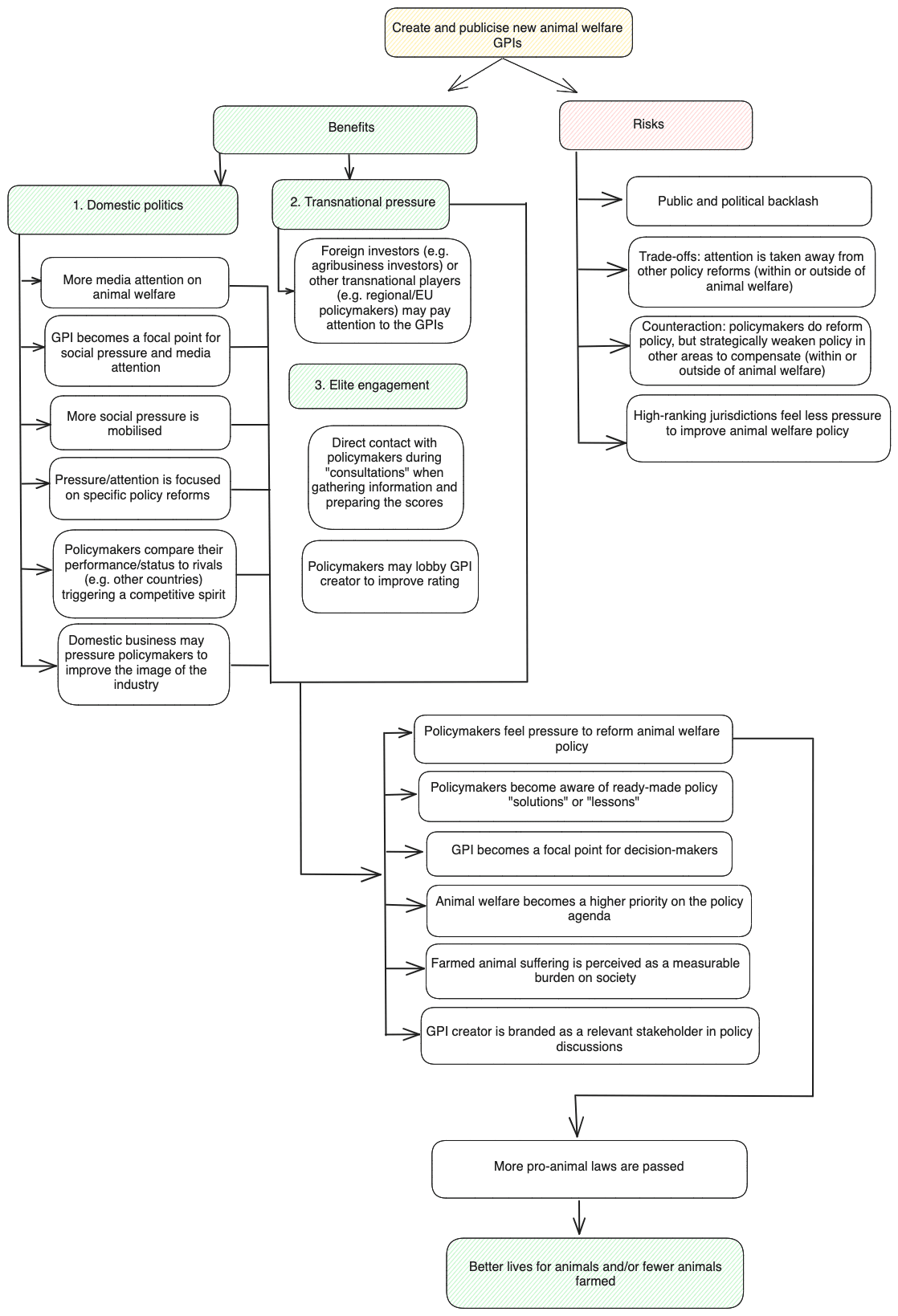

1.4 Theory of change

The following diagram summarises the main ways that GPIs could cause policy change (5,7–12). There are also some risks that can interfere with policy change (8,13–15). Not all of the mechanisms visualised in the diagram are well-supported by the evidence. The evidence behind each of these various mechanisms are discussed further in the following section.

2. Do GPIs cause policy change?

Yes, at least sometimes. The evidence suggests that GPIs can causally influence policy in a desired direction, at least occasionally and in some contexts. GPIs are similar to other forms of lobbying: definitely impactful in some cases, but difficult to measure (16).

Some of the key publications that provide evidence in favour of GPIs are as follows:

- Western (15) finds a clever way to study the causal effects of GPIs, at least in some policy contexts. The author compares states' positions in GPIs to the speed with which those states ratify various treaties. Since treaties come with a clear "adopted / not adopted" signal, the author is able to provide counterfactual evidence about whether GPIs increase the probability of policy change. The author concludes that "states in the mid-range of the indicator are faster to ratify than states that are not ranked, whereas the other categories are statistically insignificant. These findings imply that indicators matter for those in the middle, but not as much for those at the extremes."

- In a book edited by Malito et al. (7), there are many cases of GPIs that have become very powerful (e.g. Human Development Index). There is even mention of "a civil society organisation (Human Rights and Displacement Consultancy, CODHES) that does activism by producing indicators on internally displaced people and then confronts the national governments with the figures."

- The book edited by Kelley and Simmons (9) reviews the evidence of the effects of GPIs. The evidence is limited to a few policy domains, but there are some general insights. As the authors conclude: "We have shown that GPIs can influence how an issue is discussed and understood and that some GPIs have ultimately altered the content or speed of reforms in the policy areas targeted [...] Sometimes specific laws and practices change as a result of GPIs." The authors argue that GPIs "can have very real effects on the targeted state through a status mechanism". Policymakers "know that their state is being ranked", and that "their performance will be splashed across the internet", and so "they experience social pressure to conform". The authors point out that "the media is particularly fond of reporting relative rankings", so GPIs can help gain media attention for an issue. Finally, the authors emphasise the importance of the GPIs being produced by organisations that are perceived as having expertise.

- One specific chapter in that book deals with the Aid Transparency Index, created by an NGO that was "small, with nine staff members and a 2017 budget of less than £600,000", "housed in a modest one-room office above an Italian restaurant on London’s South Bank", and had "no direct material power". Nevertheless, this NGO "used its political independence and first-mover advantage to establish the gold standard for funding transparency" (9).

- Schleicher (17) reviews international GPIs with a focus on the education system. The author concludes that GPIs are a "powerful instrument for policy reform". GPIs can show what is possible; set policy targets and identify policy levers; establish trajectories for reform. GPIs transform a specialised/technical debate into a public debate. The author also gives examples in education where international GPIs have raised public awareness, engaged stakeholders in support of policy reform, and created political momentum - in many cases leading to concrete reforms. Notably, reform has typically occurred when countries score poorly, but reform has also occurred when the scores revealed specific problems that stakeholders were not already aware of (e.g. socioeconomic disparities in learning opportunities in Germany). The author does warn that "policymakers tend to use them selectively, often in support of existing policies rather than as instruments to challenge them and explore alternatives."

- Kelley (18) focuses on "scorecard diplomacy", where GPIs are embedded in traditional diplomacy. In other words, Kelley focuses on GPIs that are created by governments to place pressure on other governments. Kelley argues that GPIs have "the power to shape the reputations of states." The author provides evidence that policymakers do become upset when they receive scores that are worse than those of their peers. However, evidence that GPIs actually affect policy remains mixed, largely due to the confounded variables involved in this question.

There are also many contexts where GPIs have not appeared to cause any policy change. There are many null findings, and some GPIs never matter (9). To illustrate, Dominique et al. (19) provide a pessimistic view of GPIs, drawing on interviews with ICT policy experts in the US and Europe. The authors argue that "policy-makers use international benchmarking [GPIs] strategically to advance their agendas". Rather than allowing themselves to be manipulated by GPIs, policymakers "select those that best suit their agenda and interests, citing results that are favourable and eschewing those that are unflattering." Policymakers typically resist "adopting the 'lessons' of international comparisons" on the basis of "the exceptional nature of their national circumstances".

3. The risk of backfire

There are four main mechanisms that have been identified as potential risks of GPIs:

- Backlash. When the people in a country feel shamed by outsiders, there may be public and political backlash: "a strong, negative, public, and often angry societal reaction" (14). A negative emotional reaction can cause policymakers to become more resistant to policy change, which might actually make policy change more difficult than it was in the first place. As Snyder (8) writes, there is a "well-established risk that backlash of shaming can produce outcomes that are counterproductive for rights". This is most relevant in jurisdictions that receive a negative score. This is probably a big risk, and there is strong evidence that this does occur (8,13,20–27).

- Trade-offs. Increasing the amount of attention for specific animal welfare reforms could take attention away from other important issues (within or outside of animal advocacy) (14). This is probably not a huge risk.

- Counteraction. When policymakers do indeed reform policy, they may strategically weaken policy in other areas at the same time (14). This can allow the policymaker to meet the specific demands placed on them while compensating in other areas (e.g. keeping the industry happy overall). This is probably not a huge risk.

- The tortoise and the hare. If a jurisdiction performs well on a GPI, the policymakers in that jurisdiction may be incentivised not to adopt any new animal welfare policies (15,28,29). However, there is not much evidence that this would actually decrease the probability that jurisdictions would adopt new policies, relative to the scenario where that jurisdiction was not ranked at all.

Could these risks be a reason not to produce animal welfare GPIs? We think not—while these risks are certainly a reason to exercise caution, they are not a reason to forego GPIs altogether.

Firstly, the evidence for some of these risks is weak. Strezhnev et al. (14) argue that the "burden of proof [...] should be as rigorous as those for" the idea that GPIs work in the first place. As Strezhnev et al. conclude: "These claims may be plausible; all merit serious attention. But only a few researchers provide systematic evidence for such claims. Even fewer provide evidence that supports their causal arguments."

Secondly, there are ways that the creators of GPIs can reduce these risks. We think that the most significant risk is that of an emotional, public or political backlash—fortunately, there are characteristics that can be adopted when designing GPIs to reduce this risk. We list many of these characteristics below (see "5. Good GPI design"). We agree with the conclusion of Strezhnev et al. (14), who write in the context of human rights: "The risk of discouraging promotion of international human rights norms based on underidentified causal mechanisms is very serious indeed. Statistical science aside, we would argue that even if committing to and advocating international human rights sometimes cause some harm, this would not necessarily justify silence. Rather, it should prompt consideration of means to blunt the effects of counteraction."

4. Good GPI design

There are many characteristics that can help increase the chance that a GPI will be successful in its goals (5,7–9,14,15,20,21,23–25,28,30–33). While no GPI will have all of these characteristics, adopting the characteristics that are appropriate for the local context can increase the chance of desired policy change and decrease the chance of an emotional backlash.

Characteristics of the GPI:

- The GPI focuses on actionable policies to measure/recommend. It is clear what policies are driving the scores.

- The national policies that are measured/recommended are relevant for the local context/situation of the target (6). This might be a reason to make region-specific GPIs; expecting Uganda to adopt the same policies as Switzerland, for example, is not realistic.

- Target policymakers are made to feel like they can readily move up in the rankings, and it is clear how they can do so.

- The GPI focuses on practices with low cultural salience (e.g. animal husbandry practices that nobody feels too strongly about), rather than practices that are perceived to be important for culture and tradition (e.g. bullfighting).

- GPIs are updated and released regularly (e.g. annual reports).

- GPIs presented in a visually appealing format.

- Low-ranking jurisdictions are targeted using absolute, homogenising standards (e.g. a single category of "leading animal welfare countries" that they could join). High-ranking jurisdictions are targeted using relative standards that make explicit comparison to other countries (e.g. a numbered ranking/comparison of multiple rival countries against each other) (34).

- The GPI's creator is perceived as fair, knowledgeable, competent, and independent from political actors. The GPI's creator has existing authority and respect, especially in the culture of the target country. The organisation could be a cultural insider or a highly respected outsider.

- The target of the GPI is specific and acceptable. For example, a GPI may target specific ministries or even individual policy makers, rather than non-elite farmers or the country/culture as a whole.

- The GPI is used to place pressure on the peers of the target, especially if the target is elite. For example, a high-ranking politician may be insulated from criticism, so the GPI could instead aim to have the politician's colleagues, associates, or friends and family be the ones to place pressure on the politician.

- Target policymakers have political buy-in; they are given the opportunity to be involved in the creation of the GPI and/or to review the scores before publication.

- The target jurisdiction has an existing, functional civil society. There are enfranchised individuals and organisations who already oppose, or are not strongly attached to, the government in power.

- Criticism is respectful, focused on policy, and aimed towards solution. The criticism does not centre on character flaws.

- The GPI is framed as technical advice for solving a specific problem, not as moral criticism.

- Neither the GPI creator nor the criticism itself is perceived as threatening (e.g. farmers feeling threatened by activists; public feeling threatened by risks to food security/wealth).

- Local culture and norms are respected. Criticism is framed as an inconsistency between the target's identity (e.g. if a country values having a sustainable food system) and the poor policy performance. Alternatively, animal welfare is tied to the identity of a high-status out-group with which the target policymakers want to identify (e.g. countries that are "internationally competitive" for investments; "environmentally responsible" countries). Care is taken to reduce the ability of the target to invoke sovereignty and/or cultural traditions as justification for avoiding policy change.

Characteristics of a GPI's creator:

Characteristics of the target policymakers:

Characteristics of the way that policy critiques is framed:

5. Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA)

Basically every researcher (including us) who has published on the topic of GPIs trips over themselves to emphasise how difficult it is to measure the policy impact of GPIs precisely. The context is critical. This presents a problem if we want to understand the cost-effectiveness of GPIs.

There are two ways of looking at this problem. Firstly, we could make a back-of-the-envelope calculation. For example, let's make some reasonable assumptions:

- A GPI squad would need a couple of talented employees, together costing somewhere in the vicinity of 100,000 USD per year.

- Such a team could probably produce, say, a dozen sets of GPIs each year. We would not expect every GPI to have a policy impact. We might expect, conservatively, that one set of GPIs every few years causes a policy to be implemented where that policy would not have otherwise been implemented. It is also worth noting that each set of GPIs would target multiple countries, making this a very conservative estimate.

- Under these assumptions, it would cost the movement a few hundred thousand US dollars to buy a counterfactual policy.

- These GPIs would typically be aimed at the most numerous groups of farmed animals in a particular region, like chickens, fish or shrimp. It is standard for an averaged-sized country to have somewhere in the vicinity of 10 million chickens alive at any one time.

- If you divide the impact (millions of animal-years benefitted per year) by the costs (a few hundred thousand dollars), the number of animals helped per dollar does seem potentially high (e.g. comparable to corporate cage-free campaigns (35)). Also, after the first couple of years of operation, the GPI squad would have a much more informed view about these assumptions.

Alternatively, rather than the quantitative back-of-the-envelope calculation, we could instead consider this qualitative argument:

- We know two things with medium or high confidence. Firstly, GPIs do cause policy change, at least sometimes (see above section, "Do GPIs cause policy change?"). Secondly, producing GPIs is dirt cheap. A GPI squad could consist of just a couple of full-time staff members and an internet connection, as long as there is a way to circulate the resulting GPIs to animal advocacy organisations in specific countries.

- Therefore, the cost-effectiveness probably hinges not on the cost of producing GPIs, but the relative balance of benefits versus risks.

- We believe that the risks are probably pretty small, for reasons explained in the above section ("The risks of backfire").

- Therefore, a GPI squad is probably a worthwhile investment for the animal advocacy movement.

6. Conclusion

Here, we have considered establishing a new organisation whose sole purpose is to create GPIs for use in animal advocacy campaigns. We believe that it is a worthwhile investment for the animal advocacy movement to launch such an organisation. It would be critical for this organisation to: focus on the most numerous farmed animal populations (e.g. chickens, fish and shrimp); design the GPIs to minimise the risk of backfire; and, after a couple of years, produce a better-informed cost-effectiveness estimate to test whether it is worthwhile for the organisation to continue operating.

References

1. Broome A, Homolar A, Kranke M. Bad science: International organizations and the indirect power of global benchmarking. Eur J Int Relat. 2018 Sep;24(3):514–39.

2. Sandøe P, Hansen HO, Forkman B, van Horne P, Houe H, de Jong IC, et al. Market driven initiatives can improve broiler welfare - a comparison across five European countries based on the Benchmark method. Poult Sci. 2022 May;101(5):101806.

3. Sandøe P, Hansen HO, Rhode HLH, Houe H, Palmer C, Forkman B, et al. Benchmarking Farm Animal Welfare-A Novel Tool for Cross-Country Comparison Applied to Pig Production and Pork Consumption. Animals (Basel) [Internet]. 2020 May 31;10(6). Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ani10060955

4. Sandøe P, Hansen HO, Kristensen HH, Christensen T, Houe H, Forkman B. 8. Benchmarking farm animal welfare – ethical considerations when developing a tool for cross-country comparison. In: Sustainable governance and management of food systems [Internet]. The Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publishers; 2019. Available from: https://www.wageningenacademic.com/doi/abs/10.3920/978-90-8686-892-6_8

5. Cooley A, Snyder J. Ranking the world: Grading states as a tool of global governance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England; 2015.

6. Papaioannou T, Rush H, Bessant J. Benchmarking as a policy-making tool: from the Private Sector to the Public Sector. Sci Public Policy [Internet]. 2006 Mar 1 [cited 2023 May 30];33(2). Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/42790316_Benchmarking_as_a_policy-making_tool_from_the_Private_Sector_to_the_Public_Sector

7. Malito DV, Umbach G, Bhuta N, editors. The Palgrave Handbook of Indicators in Global Governance. Springer International Publishing; 2018. 27 p.

8. Snyder J. Human Rights for Pragmatists. Princeton University Press; 2022.

9. Kelley JG, Simmons BA. Governance by Other Means: Rankings as Regulatory Systems. International Theory. 2021 Mar;13(1):169–78.

10. Brankovic J. “Measure of Shame”: Media Career of the Global Slavery Index. In: Leopold R, Wendy E, Michael S, Tobias W, editors. Worlds of Rankings. Emerald Publishing Limited; 2021. p. 103–25. (Research in the Sociology of Organizations; vol. 74).

11. Bandola-Gill J. Statistical entrepreneurs: the political work of infrastructuring the SDG indicators. Policy Soc. 2022 Mar 22;41(4):498–512.

12. Kijima R, Lipscy PY. The politics of international testing. The Review of International Organizations [Internet]. 2023 Jun 20; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-023-09494-4

13. Snyder J. Backlash against human rights shaming: emotions in groups. International Theory. 2020 Mar;12(1):109–32.

14. Strezhnev A, Kelley JG, Simmons BA. Testing for Negative Spillovers: Is Promoting Human Rights Really Part of the “Problem”? Int Organ. 2021 Jan;75(1):71–102.

15. Western SD. Do indicators influence treaty ratification? The relationship between mid‐range performance and policy change. Eur J Polit Res [Internet]. 2022;(1475-6765.12476). Available from: https://ejpr.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/1475-6765.12476

16. Springlea R. The challenges with measuring the impact of lobbying [Internet]. Animal Ask; 2022. Available from: https://www.animalask.org/post/the-challenges-with-measuring-the-impact-of-lobbying

17. Schleicher A. International benchmarking as a lever for policy reform. In: Fullan M, Hargreaves A, editors. Change Wars. Solution Tree Bloomington, IN; 2009. p. 97–115.

18. Kelley JG. Scorecard Diplomacy: Grading States to Influence their Reputation and Behavior. Cambridge University Press; 2017. 379 p.

19. Dominique KC, Malik AA, Remoquillo-Jenni V. International benchmarking: Politics and policy. Sci Public Policy. 2013;40(4):504–13.

20. Spektor M, Mignozzetti U, Fasolin GN. Nationalist backlash against foreign climate shaming. Global Environmental Politics [Internet]. 2022; Available from: https://direct.mit.edu/glep/article-abstract/doi/10.1162/glep_a_00644/108905

21. Efrat A, Yair O. International rankings and public opinion: Compliance, dismissal, or backlash? The Review of International Organizations [Internet]. 2022 Dec 2; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-022-09484-y

22. Gallagher A. To Name and Shame or Not, and If So, How? A Pragmatic Analysis of Naming and Shaming the Chinese Government over Mass Atrocity Crimes against the …. Journal of Global Security Studies [Internet]. 2021; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jogss/article-pdf/doi/10.1093/jogss/ogab013/39677949/ogab013.pdf

23. Kohno M, Montinola GR, Winters MS. Foreign pressure and public opinion in target states. World Dev. 2023 Sep 1;169:106305.

24. Koliev F, Page D, Tallberg J. The Domestic Impact of International Shaming: Evidence from Climate Change and Human Rights. Public Opin Q. 2022 Aug 12;86(3):748–61.

25. Morrison K. Named and Shamed: International Advocacy and Public Support for Repressive Leaders. J Conflict Resolut. 2023 Mar 24;00220027231165683.

26. Terechshenko Z, Crabtree C, Eck K, Fariss CJ. Evaluating the influence of international norms and shaming on state respect for rights: an audit experiment with foreign embassies. International Interactions. 2019 Jul 4;45(4):720–35.

27. Edry J. Domestic Politics, NGO Activism, and Global Cooperation [Internet]. Leeds BA, editor. [Ann Arbor, United States]: Rice University; 2020. Available from: http://proxy.library.adelaide.edu.au/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/domestic-politics-ngo-activism-global-cooperation/docview/2559630901/se-2

28. Rumelili B, Towns AE. Driving liberal change? Global performance indices as a system of normative stratification in liberal international order. Coop Confl. 2022 Jun 1;57(2):152–70.

29. Towns AE. Norms and Social Hierarchies: Understanding International Policy Diffusion “From Below.” Int Organ. 2012 Apr;66(2):179–209.

30. Masaki T, Parks BC. When do performance assessments influence policy behavior? Micro-evidence from the 2014 Reform Efforts Survey. The Review of International Organizations. 2020 Apr 1;15(2):371–408.

31. Ringel L. The Janus face of valuation: Global performance indicators as powerful and criticized public measures. Politics and Governance [Internet]. 2023; Available from: https://www.cogitatiopress.com/politicsandgovernance/article/view/6780

32. Seabrooke L, Wigan D. How activists use benchmarks: Reformist and revolutionary benchmarks for global economic justice. Kokusaigaku revyu. 2015 Dec;41(5):887–904.

33. Tingley D, Tomz M. The Effects of Naming and Shaming on Public Support for Compliance with International Agreements: An Experimental Analysis of the Paris Agreement. Int Organ. 2022 Feb;76(2):445–68.

34. Towns AE, Rumelili B. Taking the pressure: Unpacking the relation between norms, social hierarchies, and social pressures on states. European Journal of International Relations. 2017 Dec 1;23(4):756–79.

35. Šimčikas S. Effective Altruism Forum. 2019. Corporate campaigns affect 9 to 120 years of chicken life per dollar spent. Available from: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/L5EZjjXKdNgcm253H/corporate-campaigns-affect-9-to-120-years-of-chicken-life